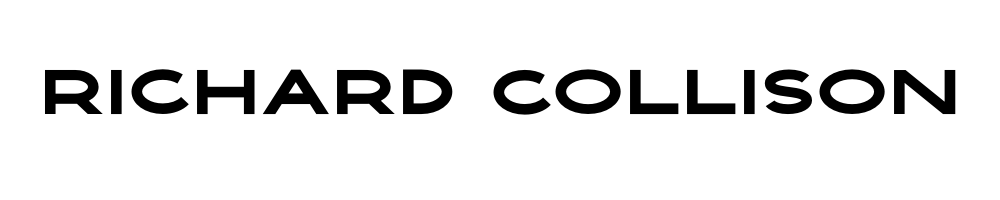

What is Art? Some ask this philosophical question after Duchamp’s famous upturned toilet. The modern art that’s popular today, what gets in the galleries and museums, is often more likely to be conceptual or abstract. But the problem with such art, as Tom Wolfe points out in his essay The Painted Word, is the ambiguity. The Artist’s Statement is often necessary to explain what art is for and what it is doing. Just like within a textbook, diagrams help explain the words. Is this what art has become, nothing more than an adjunct to terms?

‘Wolfe’s thesis in The Painted Word was that by the 1970s, modern art had moved away from being a visual experience, and more often was an illustration of art critics’ theories.’

Wikipedia source

To be considered Art today, you must sound profound about life and existence. Art often tries to be deep but could be clearer. Without words, the Art is left obscure. What distinguishes artists now is not so much their Art but their manifesto. Is this an indictment of Art, or have we finally realised what Art is?

The problem lies in the question, ‘what is art?’ It’s based on the assumption that Art is something, an essence, that makes Art what it is. We can eliminate the mystery and ambiguity if we can find and grasp this essence.

We can then answer the question. What is Art?

No Such thing as Art

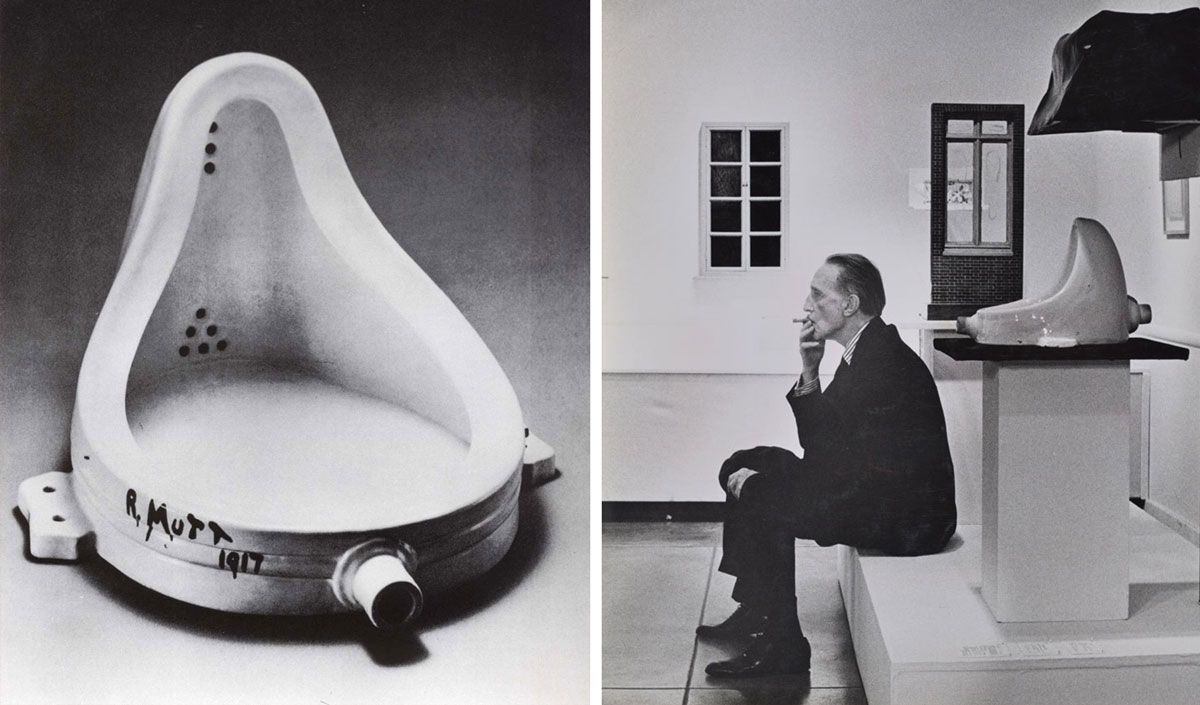

I see echoes of Buddhism here; they understand there are no essences, no fixed self to discover. Art follows this maxim; it’s not an object, and there is no substantive essence to be unearthed and studied. The essay Can Philosophy Rescue the Art World by Michael Phillips points out this idea. It’s a mistake to think Art is a thing to grasp.

‘Again, art is not a kind or a type. There are no common features that uniquely pick out everything that is, has been or will come to be called art. Instead, art objects are connected by a common history. Each subsequent stage of this history emerges out of each preceding stage, often in surprising ways. In this respect, the term ‘art’ functions more like certain proper names (‘Winston Churchill’, ‘The United States of America’) than like a general term (‘apple’, ‘gold’). Instances of art are episodes in a history, not repositories of a common essence. This means that there is no interesting atemporal account of the nature of art. In fact, there is no interesting atemporal account of the nature of most of the arts (poetry, painting, dance, music, sculpture, photography, theatre, film, novels, short stories, etc.). There are just histories of changing standards.’

Relational

Instead, art, what it is, and how we make it is more of a set of connections—a relationship. A work of art has different pieces that fit together and have differing relationships. In visual art, the composition shows the various elements included together. It’s also the Buddhist idea of Dependant Origination. All existence depends of causes and conditions of other things.

An image has meaning by it’s relation to other images. You take an ancient relic out of its place; it’s the culture, and its meaning relationship is lost, so the meaning is lost.

Here’s how Alfred Hitchcock points this out in film.

As Claude Debussy points out, ‘Music is the space between the notes’.

Art has no essence; it is how we use it, create it, and capture it. It’s a relationship that has changed and will continue to do so, art is not a thing, but a process of interconnection and transformation. It’s meaning lies in the way we use it, see it compare it, relate to it.

‘What is Art?’ has been asked for decades; here, we can finally see there is no finality, no closure, or destination to arrive at. Just the continuing relationship we have with Art, life and meaning as it unfolds.